By Jane Solomon

The word influencer has been used in English since the mid-1600s, though of course back then it wasn’t a job title. In recent years, the term has become a catch-all for a certain kind of career track that is at the center of a burgeoning but profitable industry.

As influencer continues to expand in English and pull new terms and meanings into its orbit, it is worthy of charting from a lexical perspective.

What did influencer used to mean?

For most of its existence in the language, influencer was used broadly to refer to someone or something with the power to alter the beliefs of individuals, and as a result, impact the course of events. But, when the earlier term influence entered English, it was used in reference to the movement of heavenly spheres, particularly in the context of astrology.

Styling themselves as the sages of our era, many influencers today might approve of influence’s early mystical connotations, though interest in astrology is not a requirement for the job. The modern influencer exercises their power in the less ethereal realm of social media, often strategically and for profit. And profit they do.

Influencers, who typically boast a devoted and engaged following on their social-media platform of choice, are a boon for big brands who want to get their products in front of receptive audiences in a way that seems more seamless and contextual than traditional advertising. The result is a booming industry: influencer marketing could be worth $10 billion by 2022.

It should come as no surprise then that a plethora of variations on the influencer theme, such as thought leaders, thinkfluencers, microinfluencers, and even nanoinfluencers, now vie for attention and sway on our social feeds.

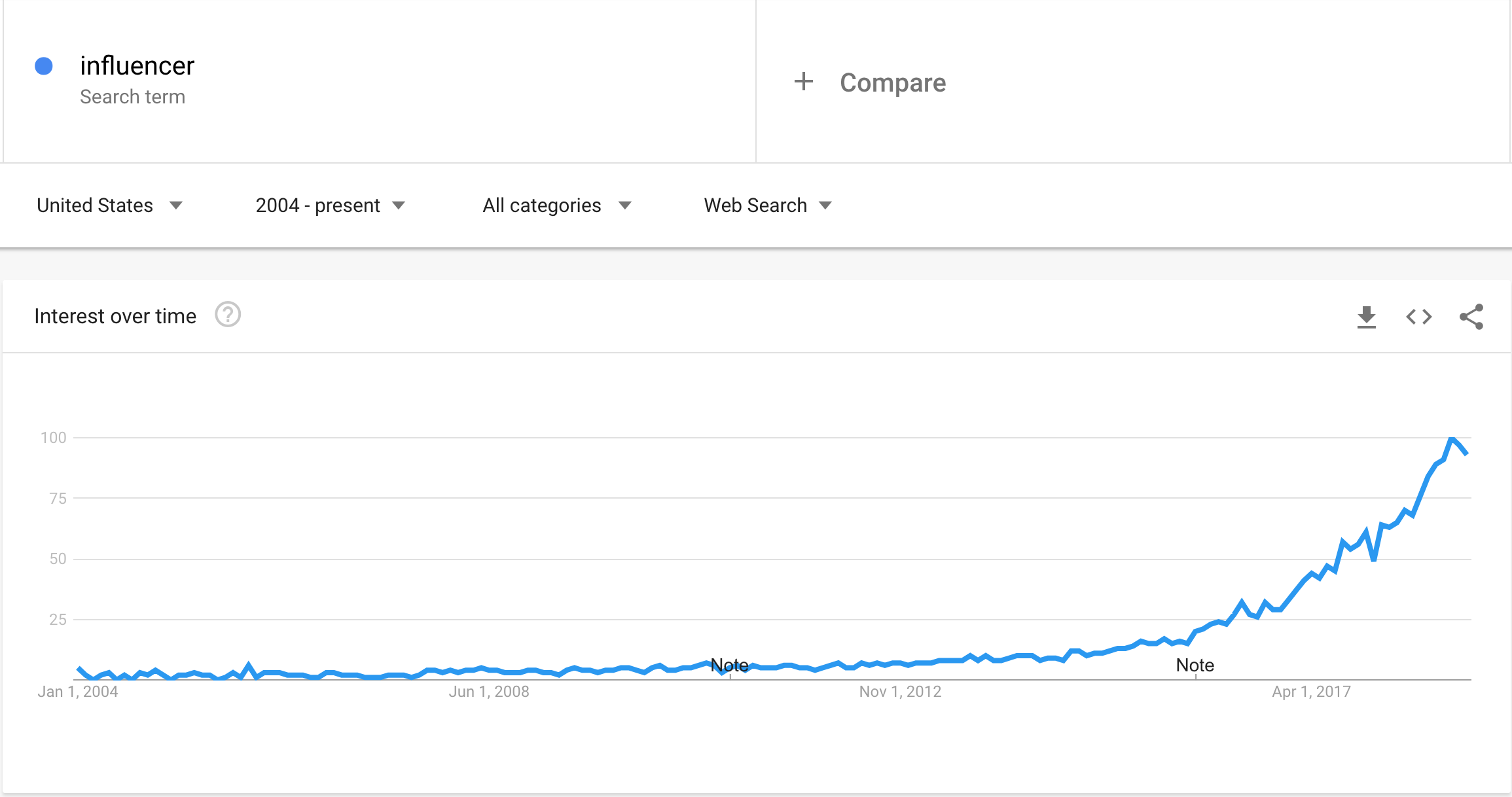

Before 2016, there was no definition for the term influencer on Dictionary.com. The term existed, of course, but before 2016, influencer culture as we now know it was only just emerging. This is reflected in searches for the term influencer on Google; interest began in late 2015 and has steadily risen over the last couple of years.

Google Trends

Are you relevant enough for sponcon?

Sponcon, short for sponsored content, has become a productive descriptor to discuss paid partnerships on social media. In a relatively short period, the culture has shifted its mindset when it comes to sponcon. As Taylor Lorenz writes in The Atlantic, “A decade ago, shilling products to your fans may have been seen as selling out. Now it’s a sign of success.” Lorenz reports that sponcon has become so popular that now wannabe influencers have started posting fake sponcon in the hopes of securing real partnerships with brands.

Sponcon con artists fabricate this content by mimicking the language, both visual and verbal, of the influencers they aspire to be. Mindful of the fact that the Federal Trade Commission has issued numerous warnings to brands and influencers over improper disclosure of material connections, these influencer-hopefuls write their posts as if the FTC were standing over their shoulders when they hit “share.”

This is because an influencer’s success hinges largely on how relevant they appear to brands and to followers. Relevant has historically described things. Now it describes people. The social currency sense of relevant comes up again and again in discussions of online behavior. Ariana Grande’s Twitter feed is a case study in this nascent sense of relevant. She wrote about her ex-fiance’s disdain for relevancy in a now deleted tweet: “For somebody who claims to hate relevancy u sure love clinging onto it huh.” She also chided Piers Morgan for his attempts at staying relevant: “…there are other ways to go about making yourself relevant than to criticize young, beautiful, successful women for everything they do.”

also @piersmorgan, i look forward to the day you realize there are other ways to go about making yourself relevant than to criticize young, beautiful, successful women for everything they do. i think that’ll be a beautiful thing for you and your career or what’s left of it. 🖤

— Ariana Grande (@ArianaGrande) November 21, 2018

Brands are people, too

Like relevant, the term brand has undergone a semantic shift. The advertising sense of brand, as in the phrase brand identity, has been around since the early 20th century (here’s a 1913 citation from an advertising journal), but until recently this sense was typically used in connection with corporations, firms, or products. Now it is often used in connection with individuals.

In May 2018, Amanda Hess wrote about the ubiquity of the personal brand for the New York Times: “Anything that can be consumed is now understood as a brand—and on the internet, that’s every last bit of content.” This statement echoes a 2015 interview on This American Life in which three teenage girls discuss their social-media interactions. One of the girls explains: “It’s like I’m– I’m a brand …”

Even brands that are not people are personified on social media. A recent fanfic explored a romantic relationship between the people who run Dictionary.com’s and Merriam-Webster’s Twitter accounts. Putting aside the fact that I would 100 percent watch that romcom, there’s something very profound happening here when people are brands and brands are people. It’s changing how we think about the world, and this naturally impacts the language we use to discuss these topics.

It's 2018. There's Dictionary Fan Fic. @MerriamWebster, @OED, we're here for it. You in? #ForbiddenLove https://t.co/FIa9THKV1U pic.twitter.com/MvXbJxifOX

— Dictionary.com (@Dictionarycom) December 10, 2018

Why have people gravitated toward the term influencer?

Of all the terms we could use to describe these social-media stars, why have we found influencer so useful? Well, to start, the term influencer has something that similar titles lack. It’s not tied to any one platform, and it’s more all-encompassing than domain-specific terms like YouTube star, Twitter personality, or gamecaster. There’s a certain heft to influencer that allows it to move beyond social-media platforms and into offline realities.

Influencer marketing is so effective in part because of its near-invisibility. Encountering sponcon on our Instagram feed next to posts from our family and friends is such an organic experience that it blurs our awareness of our role as consumer. We’re constantly being advertised to, but it’s more like our cool friend is telling us their secrets. Perhaps the weight inherent in this title is linked to the original connotations of influence—that mystery, intrigue, and divine force with the power to shift the positions of heavenly bodies.

Jane Solomon is a lexicographer based in Oakland, CA. She spends her days writing definitions and working on various projects for Dictionary.com. In the past, she’s worked with other dictionary publishers including Cambridge, HarperCollins, Oxford, and Scholastic, and she was a coauthor of “Among the New Words,” a quarterly article in the journal American Speech. She is also part of the Unicode Emoji Subcommittee, the group that decides what new emoji pop up on our devices. Jane blogs at Lexical Items, and she is the author of the children’s book The Dictionary of Difficult Words.

To read more by Jane, click below:

Where Do Our Favorite Emoji Come From?

What Is Ghosting?

The Deep Web vs. The Dark Web