What is ASL or American Sign Language?

American Sign Language, or ASL, is the visual signing language used by the Deaf community in the United States. English speakers in Canada and in a handful of other counties use ASL, too. Interestingly, those countries include the Philippines, Singapore, Jamaica, China, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cambodia, and Bolivia—a varied group. There are other sign languages (used less frequently in the US), including Signed Exact English (SEE) and Pidgin Signed English (PSE). There is also an International Sign Language (ISL), but it’s not widely used and consists of a very standardized vocabulary which doesn’t really change.

ASL is used as a common second language, or lingua franca, in Deaf communities throughout the world. And, in recent years, there has been a push to accept ASL as a “foreign language” component on college and high-school campuses in the United States. We’re not sure which is easier for the ambitious traveler to learn: a language like Mandarin or American Sign Language. But, it’s clear that ASL is recognized in more places around the world than Mandarin, so there’s that. Imagine being able to communicate with people in China, Bolivia, or Chad!

European countries have their own signing languages though, and in some cases, more than one. ASL is most similar to French Sign Language (LSF), due to the influence of LSF in the creation of ASL (we’ll get to its origins in a moment).

How did ASL originate?

Just as oral languages developed naturally and organically, so did ASL. It’s what is called a “natural language,” as opposed to a “constructed language” (such as that used in computer programming) or an “auxiliary language” (one created as a communication tool between regions, tribes, or nations).

There have long been “home-signing” languages that families developed for deaf members, and there is some evidence that Native Americans of the plains created a universal signing language to unite various tribes. But, it wasn’t until 1817, with the creation of the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, CT, that a formal sign language was instituted in the US. The origin story behind the school was that the school’s founder traveled to Europe and learned about the French Sign Language (LSF). He brought LSF (and Laurent Clerc, a teacher of the deaf from the Royal Institution for the Deaf in France) back to the states with him.

And, just as British English changed as it came to the United States, so did French Sign Language adapt to its new environment. Because of Clerc’s French background, French sign language heavily influenced ASL. But, the signs used in America at the time also played a part, particularly that of the large Deaf community on Martha’s Vineyard.

How does ASL work?

ASL, and all sign languages, allows the speaker to use concepts, not words. ASL is comprised of its own grammatical tools, with its own syntax (the formation of sentences), morphology (the patterns of word formation), and phonology (usually speech sounds; in signing, it’s the hand signals and motion). And, in the 1960s, linguist William Stokoe, a professor at Gallaudet University, proved that ASL was its own independent language because of these things.

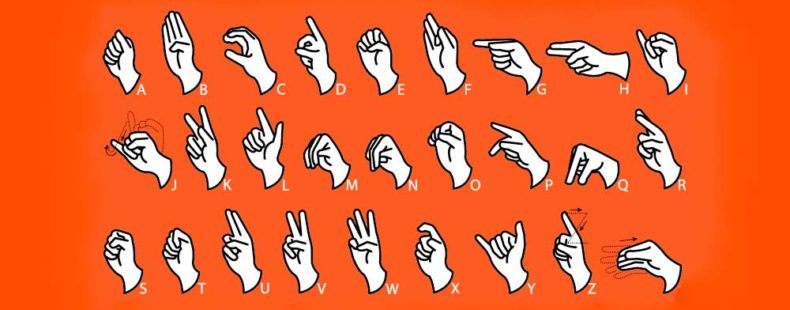

In ASL, a rich and complex vocabulary of concepts are displayed with hand signs—using one or two hands—that act as a kind of shorthand for what would be a longer, voiced sentence. The syntax is generally subject-verb-object. “Fingerspelling” uses the 26 signs for each letter of the alphabet (one handed), mostly to spell out proper nouns or for inquiring about an unknown sign.

You’ve heard “talk to the hand” plenty of times; in ASL, the speakers talk with the hand . . . and with the face and entire body. The placement or positioning of the hands has specific meaning, as does the speed and size of the gesture. Body language also colors the communication. “Non-manual markers,” such as eyebrow raising, body shifting, or head tilting can convey a lot of information.

The listener should look at the speaker’s eyes and face, while watching the signing peripherally. That may take some practice for those learning ASL, but in time one would learn that facial expressions are just as important as the signs. Plus, it’s just a better way to engage, isn’t it?

As with voiced language, there are various linguistic and dictionary-publishing agencies involved in defining the vocabulary of ASL. New signs appear on the landscape in an organic way, and after much testing and experimenting, a dominant version tends to emerge, and that’s what appears in various guides and texts. That’s pretty much how it happens for voiced language, too.

Regionalisms and ASL

Regional flavor colors ASL, just like it does in voiced language. There are dialects and accents, different terms of expression, and markers of ethnicity and age. For example, people sign slower in southern states, and concepts in one area of the country might not make sense in another. (Just as one state’s “pop” is another state’s “soda.”)

There is also a Black American Sign Language (BASL), which evolved from residential schools for the deaf during segregation. Though segregation was declared unconstitutional in 1954, it took another 24 years for all Deaf schools to desegregate. Naturally, the two versions developed some solid distinctions. BASL is generally a more old-school version of ASL, preserving many of the original signs and using broader gestures, along with more two-handed signs.

How has ASL changed over time?

The physical act of signing in many instances has also changed, usually in directional motion or spatial placement, with many signs becoming more compact. Yet, the finger spelling has stayed the same. Over time, hand placements have moved away from the face so it’s not obscured. This is a way of keeping the face open for visual and eye expression.

Does ASL have slang terms?

Of course, in both BASL and ASL, slang and colloquialisms have their place. Slang phrases created by and for the Deaf community would translate in mysterious ways to the Non-Deaf community: the sign for accept-hard means to “suck it up,” and kissfist-you is “you’re the best!” Street-language such as stop tripping are signed in BASL in ways that differentiate them from a literal meaning (in this case moving the motion to the head to indicate one’s mind or imagination). Common slang like photobomb, basic, and selfie have of course found their way into the ASL vocabulary, as well. Because what would we all do without the word selfie?