Word of the Day

lugubrious

adjective

mournful, dismal, or gloomy, especially in an affected, exaggerated, or unrelieved manner: lugubrious songs of lost love.

More about lugubrious

The source of English lugubrious is the Latin adjective lūgubris “mournful, sorrowful,” a derivative of the verb lūgēre “to mourn, grieve.” The meaning of lūgēre is closely akin to the Greek adjective lygrós “sad, sorrowful,” and both the Latin and the Greek words derive from the Proto-Indo-European root leug-, loug-, lug– “to break,” source of Sanskrit rugná– (from lugná-) “shattered” and rujáti “(he) breaks to pieces, shatters,” Old Irish lucht and Welsh llwyth, both meaning “load, burden,” Lithuanian lū́žti “to break” (intransitive), and Old English tō-lūcan “to tear to pieces, tear asunder.” Lugubrious entered English in the early 17th century.

how is lugubrious used?

The radio slid from mournful to downright lugubrious. Ridiculously lugubrious. There was even sobbing in the background. Talk about melodramatic.

Cohen’s lugubrious tones always divided opinion; for some they were intrinsic to his melancholic charms, to others a turn-off that blindsided them to the genius of his songcraft, which was always gilded, its cadences measured, its images polished.

lugubrious

mondegreen

noun

a word or phrase resulting from a mishearing of another word or phrase, especially in a song or poem.

More about mondegreen

The trouble with mondegreens is that they are usually so hysterically funny that you cannot stop citing examples of them instead of describing their “taxonomy” and history. Mondegreen was coined by the U.S. writer and humorist Sylvia Wright (1917-81), who wrote in an article in Harper’s Magazine: “When I was a child, my mother used to read aloud to me from Percy’s Reliques, and one of my favorite poems began, as I remember: ‘Ye Highlands and ye Lowlands, / Oh, where hae ye been? / They hae slain the Earl Amurray, / And Lady Mondegreen,’” the last line being a child’s mishearing and consequent misunderstanding of “laid him on the green.” Ms. Wright persisted in her idiosyncratic version because the real words were less romantic than her own (mis)interpretation in which she always imagined the Bonnie Earl o’ Moray dying beside his faithful lover Lady Mondegreen.

how is mondegreen used?

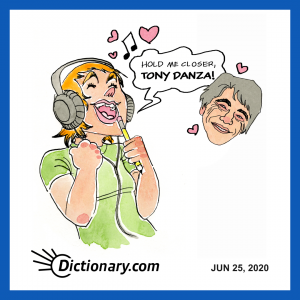

We’ve been misunderstanding song lyrics for decades, Elton John’s “hold me closer, Tony Danza”—er, “tiny dancer”—included. These funky musical mishearings even have their own name: mondegreens.

We still have mondegreen moments. Even though I know Creedence Clearwater Revival is singing, “There’s a bad moon on the rise,” lately it sounds suspiciously like “There’s a bathroom on the right.”

mondegreen

withershins

adverb

Chiefly Scot.

in a direction contrary to the natural one, especially contrary to the apparent course of the sun or counterclockwise: considered as unlucky or causing disaster.

More about withershins

All you have to remember is that withershins (or widdershins) is the exact opposite of deasil, and you’ll get back home all safe and sound. Withershins is an adverb meaning “going contrary to the natural direction, contrary to the course of the sun, counterclockwise (and therefore unlucky).” Deasil, from Scots Gaelic and Irish Gaelic deiseal “to the right, clockwise, following the sun,” is restricted to Scots. Withershins comes from Middle Low German weddersins, weddersinnes “against the way, in the opposite direction,” formed from wider “back, again” (cognate with the prefix with– in withstand) and sinnes, the genitive case (used as an adverb) of sin “way, course, direction.” Withershins entered English in the first half of the 16th century.

how is withershins used?

The fishermen, when about to proceed to the fishing, think they would have bad luck, if they were to row the boat “withershins” about.

Abel had walked slowly around the outside of the building, first clockwise and then withershins, but there was still no sign of his quarry, and the rest of the lower hollow was just as empty.

withershins