By Lindsay Barrett

Children have lots of ideas. When they begin to communicate these ideas on paper, it’s a window into their thinking that’s both endearing and fascinating.

Now, every child is unique, of course, but early writing usually progresses through recognizable stages: scribbling, pretend writing, and approximated spelling all lead up to the real thing. Here’s a rundown on what you’ll likely see between toddlerhood and early elementary school, and tips for supporting each phase.

Please note that the ages given are approximate. Children develop at different rates, and often show behaviors from more than one stage at the same time.

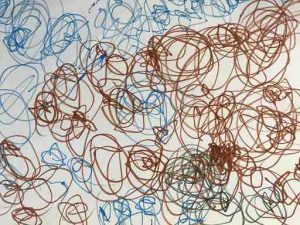

Scribbling (18 months–2.5 years)

Toddlers’ scribbling, as illustrated below, is less about content and more about how good it feels to make marks on paper. Expect to see a fisted grip and circles that go around and around, or big back-and-forth strokes across the page—or wall. Thank goodness for washable art supplies!

How to help

- Give toddlers access to chunky, easy-to-hold writing implements and large sheets of paper.

- Rather than asking, “What did you draw?” make descriptive observations, such as: “You used a lot of brown! It goes around and around!” This builds language and honors kids’ work.

Activities

- Use masking tape to secure paper to the table or high-chair tray. Give toddlers just one or two crayons (to avoid, you know, the ole “dump the crayons” game) and see what they do!

- Encourage development of a pincer grasp by giving children items they must pick up with their fingertips and thumb. This builds the muscles needed for a mature pencil grip. Think dry cereal pieces, puzzles with small pegs, or small items to plunk into the mouth of a plastic bottle. Watch for choking hazards, of course!

Meaningful marks (2.5–3.5 years)

Older toddlers and young preschoolers begin to make marks with more intention—even if that intention still requires translation. Whether you call it drawing or writing, at this stage, they overlap. Regarding her careful purple blob, this child confidently reported, “This Daddy.”

How to help

- Offer to write down children’s ideas when they talk to you about their drawings. Besides making them proud, it shows them how print carries a message.

- Continue to work on that pincer grasp. Short, stubby pieces of crayon or chalk offer natural encouragement.

Activities

- When a child is absorbed in mark-making, ask questions to encourage adding more, such as “Who else will be in the picture? Is Daddy at our house? Is the sun out?”

- Label the parts of children’s work as they point them out with legible printing. Or say, “Is this a story? How does it go?” Prompting with “Once upon a time …” can help get the story flowing. Write down children’s words and read them back.

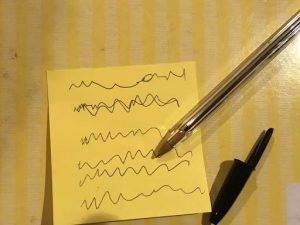

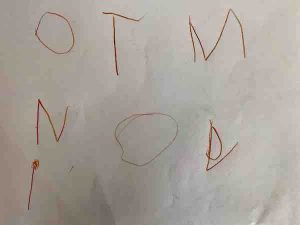

Letter-like forms and letter strings (3.5–5 years)

As they settle into preschool, children begin to pay more attention to adult writing, as well as notice the difference between print and illustrations in books. They attempt writing with writing-like scribbles, lines, and curves that resemble letters, and eventually, strings of actual letters (likely random ones). The following samples show a “rocket ship” picture labeled with letter-like forms, a “grocery list” written with mock handwriting, and a preschooler’s proud demonstration of “I can write letters, you know!”

How to help

- Show children the many functions and forms of writing: lists, cards, signs, menus, reminders, etc. If you can write it down with them watching, do it.

- Encourage children to point to and “read” their pretend writing left to right.

- When children ask how to write letters, model consistent strokes, always starting at the top.

Activities

- Familiarize children with the letters in their names and the names of family members by making a book or set of picture cards with names and faces. Point out the beginning letter of each person’s name as you browse them.

- Give children non-paper ways to practice forming letters, such as drawing letters to guess on each other’s backs, on a foggy window, or in sand or dirt. Big, broad muscle movements are great for solidifying learning.

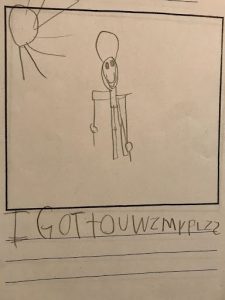

Attempted or “invented” spelling (5–7 years)

As children learn letter forms and sounds, they can attempt to spell words. When children use invented spelling, they use the sounds they hear in words to try to write them. Their attempts give useful insights into what they know about letters and sounds, or phonics.

For example, a child might attempt to spell eagle as “E,” “EGL,” or “Egul.” Encouraging invented spelling empowers children to write without relying on an adult’s assistance. Listening for and recording each sound in a word helps them learn to decode words in reading, too: Double win!

Let’s practice: what can you tell about this child’s phonics knowledge from this page (below) of his story about going skiing?

Did you notice how he knows many consonant sounds and even a short vowel sound (the O in got)? He also knows how to write a handful of high-frequency words conventionally (I, to, my). Long vowel sounds haven’t fully emerged yet; he punted on use and missed the O in poles.

How to help/activities

- Give children lots of meaningful chances to write by inviting them to label or caption their drawings, create signs, and write about their experiences and favorite topics in homemade books.

- When children ask, “How do you spell….?” bite your tongue and resist the urge to tell them. Instead, say, “Let’s say the word slowly and listen for the sounds in it.” Model enunciating each sound and recording a letter to represent it. Accept children’s efforts even if they are wrong.

A note on accuracy: Yes, it may seem ironic for the dictionary to suggest, but incorrect spellings are A-OK at this stage! Do we want teenagers writing “DGZ” for dogs in their college essays? Of course not. But, does “DGZ” let a kindergartener think about consonant sounds and experience the satisfaction of writing independently? Absolutely!

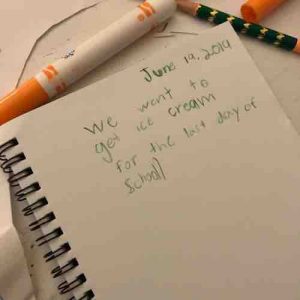

Fluent writing (7+)

The final stage of early writing is fluent, conventional writing. Forming letters and spelling words now requires less physical and mental labor. Readability improves and errors are more characteristic of common spelling patterns. (For instance, below, many words do have -ll at the end, so “schooll” is a logical attempt.) Conventions like spacing and punctuation become habits. Woo-hoo!

How to help

- Continue to support children’s spelling development by teaching them phonetic principles and about common irregular spelling patterns. For example, while the common invented spelling “-shun” may be adorable and relatable, teaching children “-tion” and “-sion” is useful and important.

- Encourage kids to transfer vocabulary and spelling learned from reading to their writing.

- Help children learn about and experiment with different writing genres. Some kids hate writing stories but love informational writing. Some kids like structured prompts while others favor the freedom of poetry.

Activities

When children share their writing with you, playfully act as the “spelling police.” Pick one or two spelling edits to use as teaching points. For instance, help correct “sed” to said throughout a story, or pick one illegible word and write it more accurately together.

It’s amazing to think that in just five years or so, a child progresses from colorful scribbles to journal entries. Be sure to save writing samples from every stage. It’s fun for children—and their caregivers—to have a record of progress!

Lindsay Barrett is a teacher and literacy consultant. She writes resources for educators and parents. Find out more about her work at lindsay-barrett.com.