Some essential terms to understand Black history

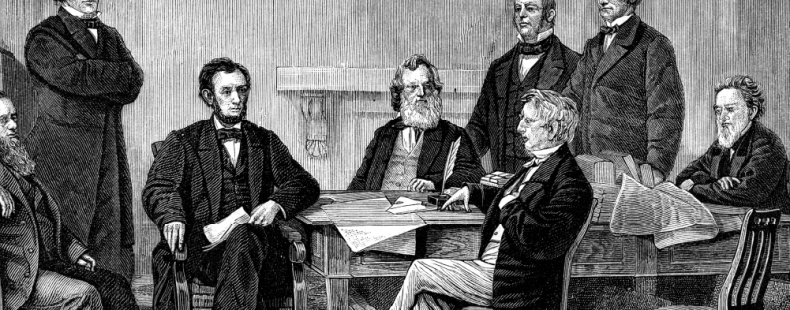

We learn about terms like Emancipation Proclamation or the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in history class. We hear about words like Juneteenth on the news. We see hashtags such as #BlackLivesMatter on social media.

But, we should always ask ourselves, how well do we know what they mean? How well do we know their history and origins, their role in the Black experience, their place in the language of American life and culture?

Black history is American history, and it’s vital we always continue or revisit our learning all year round—and not only during Black History Month. So we hope you’ll join us in this roundup of some important terms in Black history, past and present.

Why is February Black History Month? Learn more about the history behind Black History Month here!