by Rory Gory

Pansexual, skoliosexual, asexual biromantic. How young queer people are identifying their sexual and romantic orientations is expanding—as is the language they use to do it.

More than 1 in 5 LGBTQ youth use words other than lesbian, gay, and bisexual to describe their sexualities, according to a new report based on findings from The Trevor Project’s National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. When given the opportunity to describe their sexual orientation, the youth surveyed provided more than 100 different terms, such as abrosexual, graysexual, omnisexual, and many more.

While many youth (78%) are still using traditional labels like gay, lesbian, and bisexual, another 21% are exploring new words to describe—in increasingly nuanced ways—not only their sexual orientation but also their attractions and identities as well.

Young queer people are redefining sexuality and attraction in their own terms, and are leading the way in how we talk about them.

Why words matter

Finding a word to describe your sexual identity can be a moment of liberation. It can be the difference between feeling broken and alienated to achieving self-understanding and acceptance. And when specifically describing one’s sexuality to others, labels can help create a community among those who identify similarly and facilitate understanding among those who identify differently.

Words to describe the specifics of one’s sexual and romantic attractions (affectional orientation) are becoming more important to younger generations. Anticipating The Trevor Report’s findings, the trend forecasting agency J. Walter Thompson’s Innovation Group found in 2016 that only 48% of youth in Generation Z identify as exclusively heterosexual, compared to 65% of millennials.

How do you define sexual orientation?

Whether you’re within the queer community or not, we all have a sexual orientation, or “one’s natural preference in sexual partners”—including if that preference is to not have any sexual partners, as is true of many in the asexual community.

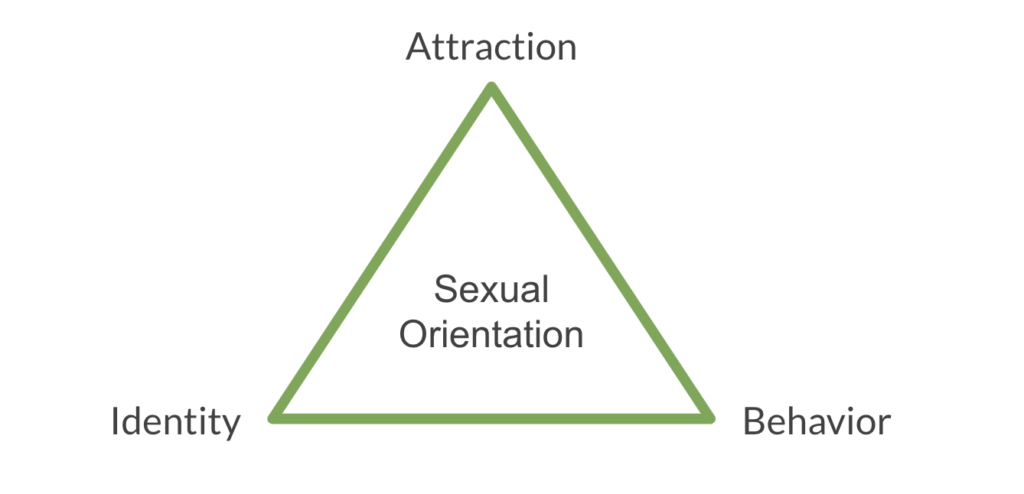

Sexual orientation is a highly individual and personal experience, and you alone have the right to define your sexual orientation in a way that makes the most sense for you. Sexual orientation is also a complex intersection made up of different forms of identity, behavior, and attraction.

Identity

Gender identity may influence your sexual orientation, but it’s important to remember that sexual orientation and gender identity are not the same thing. A person has a sexual orientation, and they have a gender identity, and just because you know one doesn’t mean you automatically know the other.

But in discovering your gender, you may redefine your sexual orientation in new ways. This experience can be true for transgender people, who may undergo changes in their sexual orientation after their transition—or who may change their labels, such as a woman who adjusts her label from straight to lesbian to describe her attraction to other women after transitioning.

Our identities cannot be put into one single box; all of us contain many different types of social identities that inform who we are. This is, in part, why Dr. Sari van Anders, a feminist neuroendocrinologist, proposed the Sexual Configurations Theory to define sexual identity as a configuration of such factors as: age and generation; race and ethnicity; class background and socioeconomic status; ability and access; and religion and values. Anders’s theory takes into account how our many identities factor into our sexual identity, and recognizes that our sexual identities can be fluid too.

Behavior

Sexual behavior also influences how we discover and define our sexual orientation. But, who you’re currently dating or partnered with, or who you’ve had sex with before, does not dictate your sexual orientation. Nor does it fully define who you are and who you can be.

Someone may have sexual experiences with a certain gender without adopting any label for their sexuality. Someone may have had a traumatic sexual experience, such as sexual assault, with a gender that has no bearing on how they self-identify. A person may have attractions they’ve never acted on for various reasons. An asexual person may have engaged in sexual activity without experiencing sexual attraction. Sexual and asexual behavior all inform one’s sexual orientation but do not define it.

Attraction

We most often think of attraction purely in sexual or physical terms, but it also includes emotional, romantic, sensual, and aesthetic attraction, among other forms. For example, a sapiosexual (based on the Latin sapiens, “wise”) is a person who finds intelligence to be a sexually attractive quality in others.

Attraction also includes the absence of attraction, such as being asexual or aromantic, describing a person who doesn’t experience romantic attraction. (The prefix a- means “without, not.”) Unlike celibacy, which is a choice to abstain from sexual activity, asexuality and aromanticism are sexual and romantic orientations, respectively.

Why is there a new language of love and attraction?

Sapiosexual and aromantic highlight ways in which people, especially LGBTQ youth, are using newer words to express the nuances of sexual and romantic attractions—and the distinctions between them. Many assume a person’s sexual orientation dictates their romantic orientation, or “one’s preference in romantic partners.” But romantic and sexual attraction are separate, and sometimes different, forms of attraction.

While many people are both sexually and romantically attracted to the same gender or genders, others may have different sexual and romantic desires. Someone who identifies, for instance, as panromantic homosexual may be sexually attracted to the same gender (homosexual), but romantically attracted to people of any (or regardless of) gender (panromantic, with pan– meaning “all.”)

Asexuality is not a monolith but a spectrum, and includes asexuality but also demisexuality (characterized by only experiencing sexual attraction after making a strong emotional connection with a specific person) and gray-asexuality (characterized by experiencing only some or occasional feelings of sexual desire). And, quoisexual refers to a person who doesn’t relate to or understand experiences or concepts of sexual attraction and orientation. Quoi (French for “what”) is based on the French expression je ne sais quoi, meaning “I don’t know (what).”

While asexual people experience little to no sexual attraction, they, of course, still have emotional needs and form relationships (which are often platonic in nature). And, as seen in a word like panromantic, the asexual community is helping to contribute a variety of terms that express different types of romantic attractions. Just like all people, an asexual person can be heteroromantic, “romantically attracted to people of the opposite sex” (hetero-, “different, other”) or homoromantic, “attracted to people of the same sex” (homo– “same”). They may also be biromantic, “romantically attracted to two or more genders.”

As more people identify as trans or nonbinary, words like androsexual (andro-, “male”) and gynesexual (gyne-, “female”) describe sexual attraction to gender expressions or anatomy, regardless of how a person identifies their gender. Someone who identifies as androsexual is attracted to masculinity or male anatomy. Someone who identifies as gynesexual is attracted to femininity or female anatomy.Androsexual and gynesexual do not define the gender of the person being labeled the way the words lesbian (a female homosexual) or gay (a homosexual person, especially a male) do. These terms can be easier for gender-fluid people to use. Sexual orientation can be fluid, too, as describes the experience of an abrosexual person, whose sexuality could be fluid, for example, between bisexuality and homosexuality.

Certain genders and body parts may play a large role in many people’s sexual orientations, but others may be specifically attracted to people with nonbinary genders. The word skoliosexual is defined as an attraction to people who identify with a nonbinary gender. Skolio– is based on a Greek root meaning “bent” or “curved”; negative associations with these words have compelled some to use the term ceterosexual instead, with cetero– based on (et) cetera, cetera meaning “the rest.”

Defining relationship types

Some young people are beginning to clarify not just their sexual orientation, but also their preferred relationship type. For example, a person who identifies as pansexual nonamorous is sexually attracted to all genders (or regardless of) gender (pansexual) and does not seek any form of committed relationship (nonamorous).

The importance of clarifying the relationship type that you prefer can help dispel common misconceptions that the genders you are attracted to dictate the number of partners you desire, such as the myth that all bisexuals are polyamorous.

In the write-in portion of the The Trevor Project’s survey, youth used nuanced language to explain the complexity of their sexual orientations and desired relationship type, such as one youth who replied “I’m a [grayromantic] polyamorous homosexual.” This young person identified their romantic attraction (grayromantic, or “occasionally experiencing romantic attraction”), sexual attraction (homosexual), and the number of partners they prefer (polyamorous, “involving multiple consensual romantic or sexual partners”). Grayromantic polyamorous homosexual paints a far more specific picture than just gay does.

One may also prefer solo sex and romance, such as those who identify as autosexual or autoromantic (auto-, “self”). A person may desire many sexual partners of any gender, but zero romantic relationships, which can be identified as non-monogamous aromantic pansexual.

You don’t have to be queer to use more specific terms to describe the number of partners you prefer or the relationship type you desire. An individual whose identity more closely conforms to current societal norms, such as a straight, cisgender, married woman, could also describe her sexuality in more specific terms, such as a monogamous heteroromantic heterosexual woman. This means she desires one partner of the opposite gender, to whom she is both sexually and romantically attracted.

Beyond labels

Despite the proliferation of labels, there are still many who choose not to identify. Of the 52% of Generation Z that doesn’t identify as specifically straight, many eschew labels altogether.

For many whose identities are fluid, living without a label can be more liberating than adopting one. For others who are questioning or exploring their sexuality, going without a label is more comfortable than committing to one that doesn’t quite fit.

Defining yourself

Unique labels—including the lack thereof—allow us to speak to the differences in our lived experiences. We do not all experience the world in exactly the same way, and we should feel free to describe our individuality using the words that do that best.

You are the expert of your experience, and know better than anyone else how you feel, what you value, and what you need. You deserve to use as many or as few words as you want when describing your unique understanding of your sexuality.

And it’s OK to use different labels depending on the situation, too. If a person is concerned for their safety, they may choose to disclose very little or nothing about their identity. Or, if someone is speaking to a person unfamiliar with the LGBTQ community, it may be easier for them to use labels such as gay, lesbian, or bisexual.

Sexual and romantic relationships are a huge part of our lives. These relationships are often the most important ones we have, building the foundations of our families and support systems. New words are an exciting way to help you discover, understand, and express your sexual orientation and attraction—and new words help give us the freedom and power to define ourselves.

Rory Gory is the Digital Marketing Manager for The Trevor Project, the leading national organization providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer & questioning (LGBTQ) young people under 25. If you or anyone you know is in crisis, reach out to The Trevor Project for support at: thetrevorproject.org/help.Read more from Rory Gory on Dictionary.com in their articles: “What Does It Mean To Be ‘Asexual’?” | “How The Letter ‘X’ Creates More Gender-Neutral Language” | “Why Is ‘Bisexual’ Such A Charged Word?”